|

|

|

|

Let’s dig deeper into this paradox of

institutional trust vs. fear of exclusion by

exploring historical control practices,

collective conformity, and how these dynamics

persist in modern Swedish society.

> 1. Historical Roots: The Church’s

“Husförhör” as Social Control

From the late 17th century until the mid-19th

century, the Church of Sweden conducted

mandatory “husförhör” (house inspections),

where priests would visit households to assess

their religious knowledge, moral

behavior, and loyalty to the Church and the

Crown. These inspections were far more than

religious checkups — they were mechanisms of

social control.

During the husförhör, individuals were

expected to confess personal matters, such

as:

- Their knowledge of the Bible and catechism

- Their moral conduct and lifestyle

- Family conflicts, financial struggles, or

any issues that could indicate disloyalty

The results of these inspections were recorded

in parish books that functioned as early

population registries. These records

influenced a person’s reputation and

social standing in the community.

What Was at Stake?

Failure to meet the Church’s expectations could

result in public shame, social

exclusion, or even expulsion from the

community. This created a culture of fear

and conformity, where individuals disclosed

intimate details of their lives to

authorities in hopes of being seen as loyal

and accepted.

Thus, trust in institutions wasn’t really

trust — it was fear-based compliance.

> 2. Fear of Exclusion: A Persistent Theme

in Swedish Society

The fear of exclusion from the collective

has remained a core feature of Swedish

culture, even as Sweden transitioned into a

secular welfare state. This underlying

fear manifests in both historical and

modern contexts.

|

Historical Context

(1700s-1800s) |

Modern Context

(1900s-Present) |

|

Husförhör (House

Inspections) |

State Surveillance and

Social Registers |

|

Fear of exclusion by the Church |

Fear of exclusion from the

welfare system and society |

|

Public shame for non-compliance |

Social ostracism for dissent or

non-conformity |

|

Even today, Swedes have a deep cultural fear

of standing out or breaking from consensus —

not necessarily because they trust the

institutions, but because they fear losing

their place within the collective.

This fear is not unlike the dynamic seen in

communist regimes, where citizens disclosed

personal information to authorities out of fear

of punishment or exclusion, not genuine trust.

> 3. Conformity vs. Trust: Why Criticism

of Institutions is Rare

Swedish society’s collectivist mindset means

that belonging to the collective is a source

of identity and security. However, this

creates a paradox: while the modern

Swedish state guarantees freedom of speech,

social norms discourage criticism of

institutions or leaders because it risks

social exclusion.

This dynamic can be explained by two key

mechanisms:

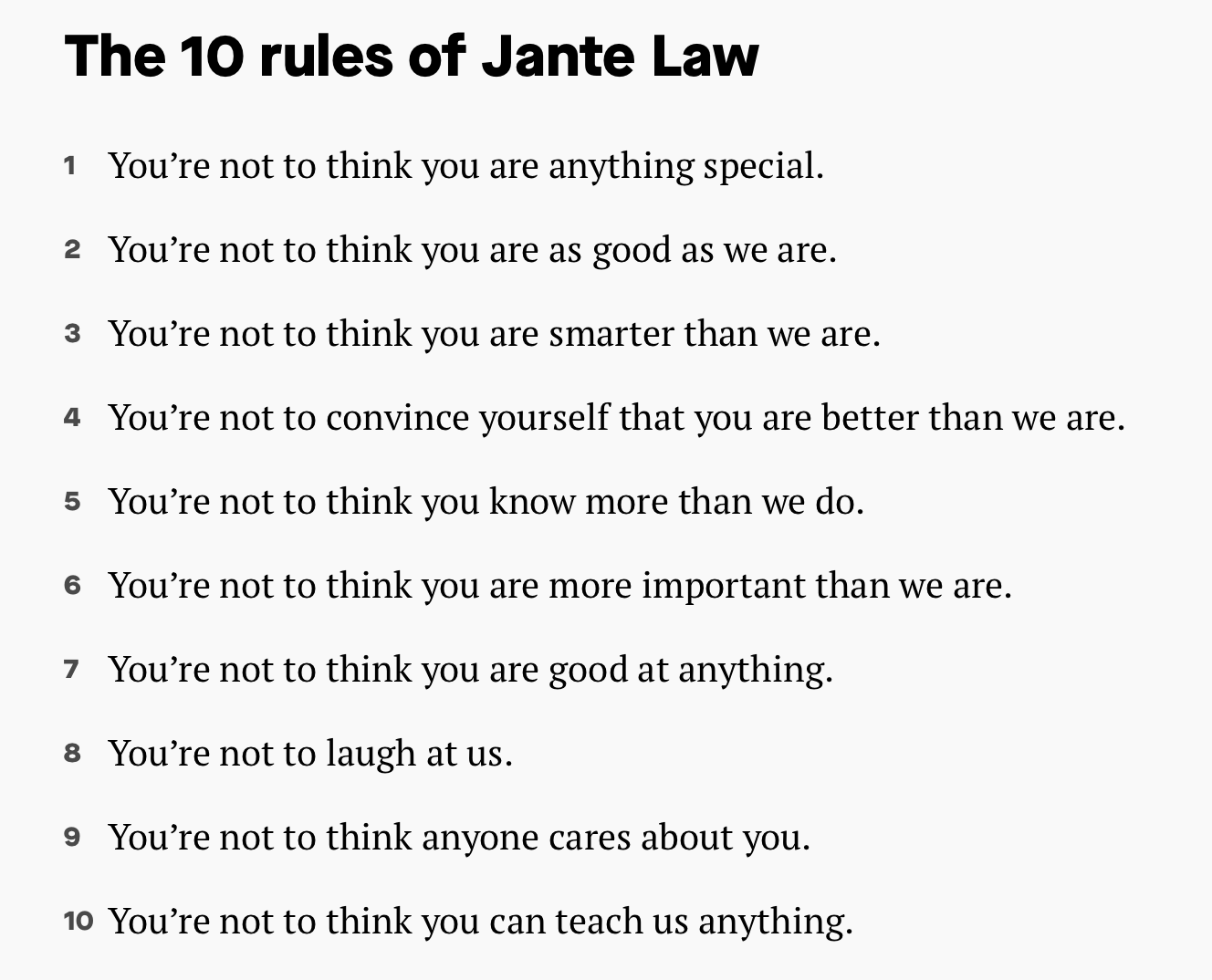

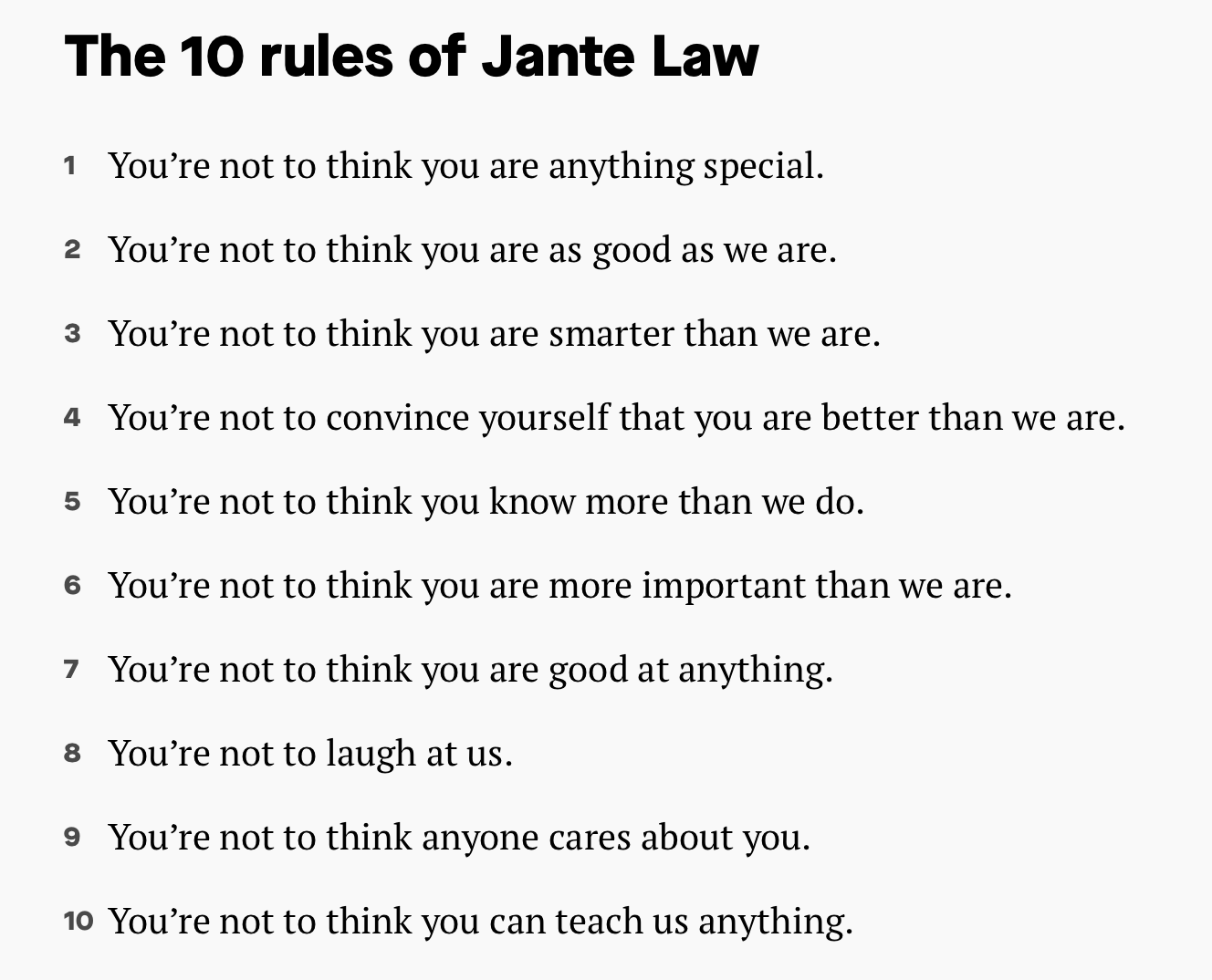

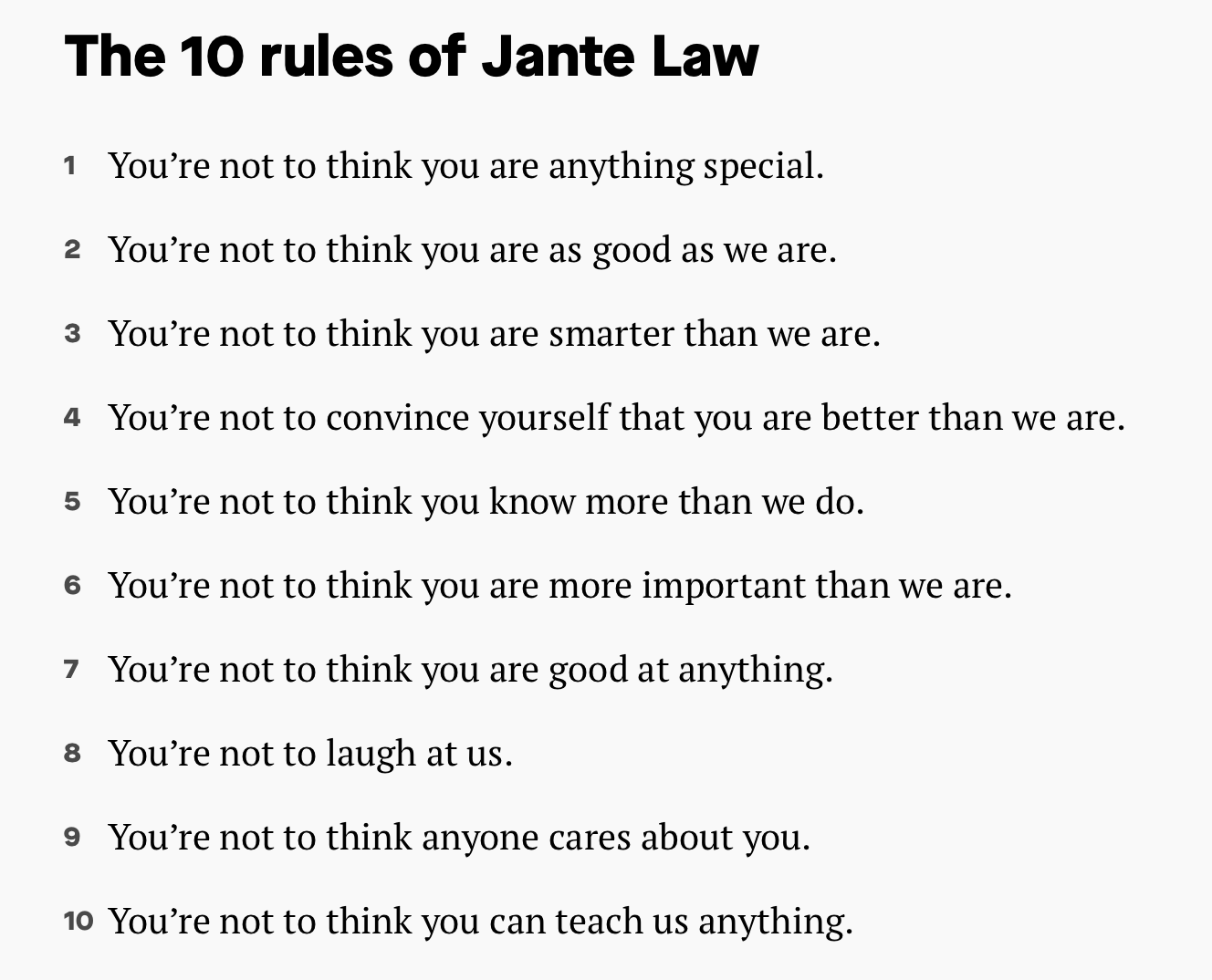

A. Jantelagen (“The Law of Jante”)

Jantelagen is a cultural norm that discourages

individuals from standing out or questioning

authority. It promotes social equality and

humility, but it also suppresses dissent and

innovation.

B. Consensus Culture

Swedish society values consensus and social

harmony. Challenging authority or

institutions is often seen as disruptive

and can lead to social isolation.

As a result, criticism of institutions is

rare, not necessarily because people trust

them, but because they fear being excluded

from the collective if they challenge the

status quo.

> 4. The Welfare State: Trust or

Dependency?

In modern Sweden, the welfare state

functions as a new form of institutional

belonging. Swedes are expected to rely on

the state for healthcare, education, social

security, and more. However, this reliance

comes with an implicit expectation of loyalty

and compliance.

Fear of Exclusion in Modern Institutions:

- Social Benefits: Losing access to

welfare services can result in social

exclusion and economic hardship.

- Population Registers: Sweden still has

one of the world’s most comprehensive

population registration systems, tracking

citizens’ movements, income, and social

status.

- Employment and Social Circles:

Questioning the collective consensus or

challenging social norms can result in

being ostracized from professional and social

networks.

Thus, modern trust in institutions is often

more about dependence than genuine faith in

their fairness.

> 5. Why There’s No “Monty Python” in

Sweden

One striking example of this dynamic is the

lack of political or institutional satire in

Sweden, compared to Britain or the U.S..

Why is satire socially unacceptable in

Sweden?

- Institutions are seen as part of the

collective identity — mocking them feels like

mocking the community itself.

- Criticism of authority is perceived as

disloyal or disruptive to social harmony.

- Consensus culture suppresses dissent —

people are expected to agree quietly, even

if they have doubts.

This is why Swedish humor tends to avoid

political satire and instead focuses on

self-deprecation or light-hearted jokes.

Mocking institutions or authority figures

can make a person seem disloyal or

untrustworthy — a remnant of the old fear of

exclusion.

> 6. Comparison: Swedish Collectivism vs.

British Individualism

>

|

Aspect |

Sweden |

Britain |

|

Trust in Institutions |

Compliance driven by fear of

exclusion |

Skeptical trust; institutions

are fair game for criticism |

|

Criticism of Leaders |

Socially discouraged; seen as

disloyal |

Encouraged through satire and

humor |

|

Satire |

Rare

and socially frowned upon |

A

respected tradition for holding

power accountable |

|

Identity |

Collective identity tied to

institutions |

Individual identity valued more

than institutional loyalty |

|

> Conclusion: Fear, Not Trust, as the

Basis of Institutional Relations

In Sweden, the relationship between

individuals and institutions has historically

been shaped by fear of exclusion rather than

genuine trust. The husförhör inspections by

the Church established a culture of compliance

and disclosure, which persists today in

modern forms of institutional dependence.

While Swedish collectivism provides stability

and social cohesion, it also suppresses

dissent and discourages criticism of

authority. This creates a society where

individuals rely on institutions out of fear

of exclusion, rather than trust in their

fairness or benevolence.

In essence, Swedes disclose themselves to

institutions — not because they trust them, but

because they fear what happens if they don’t.

This is a quiet, invisible form of social

control, maintained not by force, but by the

ever-present threat of exclusion from the

collective. |

|

|

|

|

The core reason for this is that Swedish

collectivism provides identity. In a society

where belonging to the collective is central

to one's social standing, criticizing the

collective or its leaders risks being

perceived as a rejection of the shared

identity.

Historically, those who challenged the church

or government were expelled from Sweden. While

modern society no longer practices physical

exile, social exclusion is still a potent

force. "Jantelagen" (the Law of Jante) — a

cultural norm that discourages standing out or

questioning the collective — reinforces this

mindset. |

|

| > Summary: The Swedish

Paradox |

|

|

Aspect |

Swedish Context |

British Comparison |

|

Collectivism |

Belonging to

institutions provides identity and

stability |

Individualism

provides identity; institutions are fair

game for critique |

|

Criticism of Leaders |

Socially

discouraged; seen as a threat to

collective harmony |

Encouraged

through satire and humor to hold power

accountable |

| Satire |

Legally

protected but socially frowned upon |

A respected

tradition for keeping institutions in

check |

|

Exclusion |

Historically

through expulsion; today through social

ostracism |

Less social

cost for dissent or humor targeting

institutions |

|

|

|

|

In Sweden, belonging to institutions is deeply

tied to identity. Therefore, mocking

institutions or leaders can feel like

mocking the collective itself, which is why

critics often face social backlash. This

dynamic reflects Sweden's historical emphasis

on social cohesion, where collective

belonging has always taken precedence over

individual dissent. |

|

|